One of the many shortcomings in our current approach to pricing legal services is the preoccupation with merely pricing the job. While at face value this would appear to be all that is required, it is in fact only half of the calculation. The other half of the equation is pricing the client.

Pricing is contextual. Put simply, this means that legal services do not have an abstract value. To the extent that anything has value, someone has to be willing to buy it and the ‘value’ will be determined by what that person is willing to pay for it.

Like almost every other product or service, legal services only have a value;

Put another way, the value of what we do is subjective and value, like beauty as the saying goes, is in the eye of the beholder.

Amongst the many factors unique to the particular client and the set of circumstances will be that client’s price sensitivity or to use another phrase adopted by pricing specialists, willingness-to-pay.

If we bring that reasoning full-circle then we inevitably get to dynamic pricing, otherwise known as surge pricing. A working definition is; ‘the practice of pricing something at a level determined by a particular customer’s perceived willingness and ability to pay.’

We experience it when we order an Uber taxi during rush-hour traffic or on a Saturday evening in the city. We sometimes experience it with changing ticket prices for major sporting or cultural events. We also experience it as we strap ourselves into our airline seat in the certain knowledge that everyone around us has probably paid a different price for their ticket.

In fact, its deployment in our day to day lives is ubiquitous without as consciously considering it.

It makes no sense therefore to attempt to price a piece of legal work without also ascertaining the context within which it sits, one component of which is the client’s willingness-to-pay and their price sensitivity.

This however begs the question ‘how does one ascertain a client’s price sensitivity and willingness-to-pay?’ Well, you could ask them but aside from the fact that they are likely to look sideways at you, it is unlikely to elicit a reliable response.

At a work stream level, it is possible to research this with a technique such as conjoint analysis. ‘Conjoint analysis’ is a survey-based statistical technique used in market research that helps determine how people value different attributes (feature, function, benefits) that make up an individual product or service.

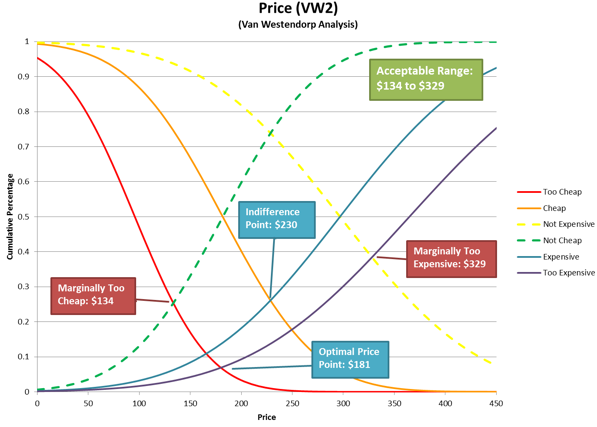

Another option at work stream level (ie. not individual client or matter level), is to undertake a Van Westerndorp price sensitivity analysis. This is achieved by asking a series of questions;

When plotted on a table, the results tend to look like this;

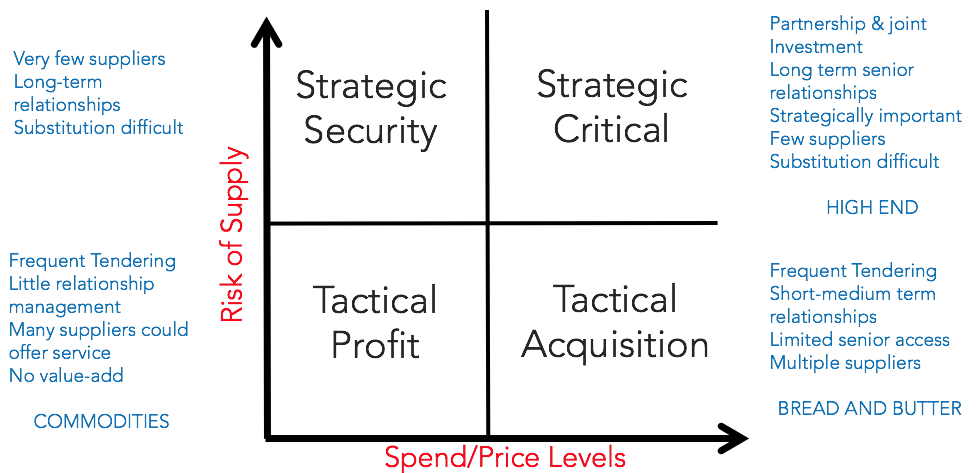

Another tool that can be very helpful in understanding the strength and depth of the firm’s relationship with a client is the Kraljic Matrix. An adapted form of the matrix is used by legal procurement professionals to segment law firms by mapping them against two key dimensions: risk and price/spend level. Clients will rarely share that with you but firms can and should do their own analysis to figure out where they think the client has placed them on that matrix.

For each of your major clients, you can be confident that they have placed you in one of these four quadrants and quite possibly different quadrants for different work streams that you supply to the client. [Thanks to my Validatum senior procurement colleague Steph Hogg for this diagram].

And finally, most of us are familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs.

We have synthesised these three frameworks to construct a visual representation in a single diagram, designed to assist firms to;

So, we are pleased to introduce to the market for the first time, the Validatum Price Sensitivity Hierarchy.

Within the overall context of the relationship, firms should develop a robust understanding of its pricing strength with any particular client. Misalignment or misunderstanding of where the firm sits on the hierarchy can result in it overplaying its hand, running the risk of either dissatisfaction through a perceived lack of value or worse, a decision by the client to investigate more cost-effective alternatives.

Alternatively, failure to understand the real strength of the firm’s relationship with the client will invariably result in pricing concessions being made that are unnecessary because they are the product of misconceived pricing weakness and lack of negotiation strength.

As can be seen from the hierarchy, there is a very strong correlation between the different value layers and a client’s price sensitivity/willingness-to-pay. That may not in itself come as a great surprise, but it is nonetheless essential to apply structure to any such analysis rather than simply ‘gut feel’ and the intuition of those responsible for managing the relationship.

What may be a little more surprising is that for most clients, table stakes and relatively high price-sensitivity tend to correlate with objective delivery criteria. Conversely, it is the less tangible, harder to define and quantify subjective aspects of the relationship that often distinguish firms that can legitimately lay claim to David Maister’s exalted position of ‘trusted advisor’ status, in contrast to those that simply ‘do a good job’.

Unfortunately, there are still too many firms that cling to the belief that all that is required to keep a client happy is to ‘do good legal work’.

You can also read Richard’s article on the Validatum website, by clicking here.