There is a quite extraordinary paradox at play here. On the one hand you would expect many lawyers, particularly those that are long in the tooth, to be quite pessimistic, negative and cynical with a hardwired expectation that most things go badly (and indeed many are, and they often do).

There is a quite extraordinary paradox at play here. On the one hand you would expect many lawyers, particularly those that are long in the tooth, to be quite pessimistic, negative and cynical with a hardwired expectation that most things go badly (and indeed many are, and they often do).

So why the perennially ebullient display of optimism when it comes to assessing the production cost of a piece of work?

When working with partners to assist them on a specific pricing proposal, all too often the conversation goes something like this;

“So what levels of resourcing will be required for this and how long do you think it’ll take?”

“Well, with a fair wind and assuming all goes well and the other side isn’t difficult and my client takes a reasonable position, and if Hayleys Comet doesn’t strike…”

“Stop, stop, when has anything ever gone well in your entire career?”

“Well, now that you mention it, never!”

There is a quite extraordinary paradox at play here. On the one hand you would expect many lawyers, particularly those that are long in the tooth, to be quite pessimistic, negative and cynical with a hardwired expectation that most things go badly (and indeed many are, and they often do).

So why the perennially ebullient display of optimism when it comes to assessing the production cost of a piece of work? [Note that I didn’t say the price of a piece of work but rather, an understanding of the production cost – two completely different things].

Part of the explanation lies in the partner’s inclination to avoid a price, which is sufficiently high that they are unlikely to get the particular piece of work.

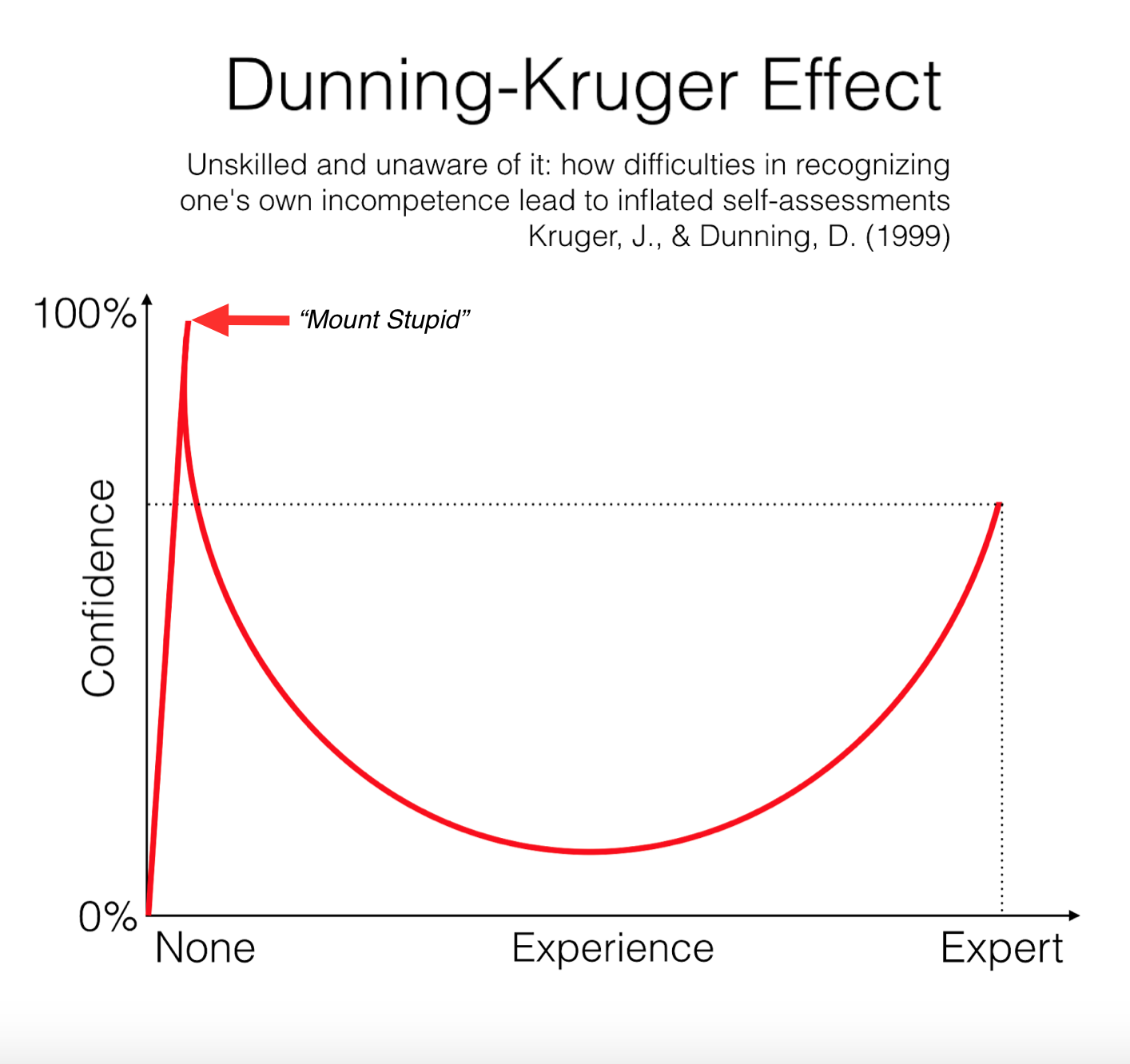

However we have never felt that this was the whole of the explanation but we think we may have stumbled across another piece of the puzzle – Dunning Kruger Syndrome. At first blush, it does rather look like a rare and malevolent strain of pathogen but happily it is rather more benign. Having said that, sufferers of Dunning Kruger Syndrome will always struggle to be competent at value pricing. But first, let me explain.

David Dunning and Justin Kruger of the department of psychology at Cornell University first observed the phenomenon in a series of experiments in 1999. The study was inspired by the case of McArthur Wheeler, a man who robbed two banks after covering his face with lemon juice in the mistaken belief that, because lemon juice is usable as invisible ink, it would prevent his face from being recorded on surveillance cameras.

This pattern of over-estimating competence was seen in studies of skills as diverse as reading comprehension, practicing medicine, operating a motor vehicle, and playing games such as chess or tennis. Dunning and Kruger proposed that, for a given skill, incompetent people will:

We can probably all think of one or two people that suffer from this version of the syndrome!

However, it is the other aspect of their finding that may go some way towards explaining why some lawyers approach pricing the way they do, and that is that high-ability individuals may underestimate their relative competence and may erroneously assume that tasks that are easy for them are also easy for others or at least are likely to be perceived by others as being easy.

This often leads to practitioners making comments like, “Oh, it should only take me a couple of hours so perhaps £700-£900”.

There are two problems with that mindset:

(a) Displaying all the characteristics of Dunning Kruger Syndrome, the partner convinces themselves that the piece of work is not a big deal as they can knock it out in a couple of hours or so because (for them!) it is relatively straightforward. This ignores the fact that it may only be relatively straightforward for them because they are expert in the field and have 25 years experience of that particular issue. People who are good at what they do make it look easy.

(b) With this mindset, despite the potentially significant value that that piece of work might deliver to the client in both financial and non-financial terms, the partner has artificially proscribed their pricing parameters by reference to the time/production cost.

This issue is at the heart of the distinction between value pricing and cost plus pricing. While we continue to contend that it is essential to understand one’s production costs at a practice area, fee earner, client and matter level, the imperative to move towards value billing continues to gain momentum, particularly with the advent of increased efficiency technology. We dealt with this issue in a recent blog post, ‘The Pricing Perfect Storm: AI and Hourly Billing’.

As an expat Kiwi living and working in London, I hope I may be indulged a little home town parochialism. The issue brings to mind a delightful line from a New Zealand High Court decision;

“If Counsel is entitled to say ‘I have reached some degree of seniority and therefore I am entitled to $x for every hour that I am professionally engaged’, then the incompetent will be encouraged to be prolix and dilatory and the efficient and truly skilled will be inadequately rewarded.”

re JBL Consolidated Limited (in receivership)

(High Court Auckland, 1950/80, 20 August 1982)

You can also read this article on the Validatum website by clicking here.