Are you providing too much background, in your legal case reports? Or not enough context and leaving the reader mystified? Sue Bramall, marketing consultant at Berners Marketing looks at a formula for case law reports proposed by US lawyer and lexicographer Bryan Garner …

Manila file folders stacked on a desk.

I came across this wonderful article entitled ‘There’s a formula for effectively explaining caselaw’ published on www.abajournal.com. I often find myself rewriting articles about case outcomes and tend to use a structure, so I wondered how this might compare to the ‘formula’ used by Bryan Garner, an American lawyer, author, professor, grammarian, and lexicographer (someone who compiles dictionaries) – a veritable expert in legal content writing.

It is heartening to read that Mr Garner, who clearly knows his onions, describes writing about case law as ‘surprisingly tricky’ while he highlights two potential weaknesses:

He demonstrates this with a vivid story of meeting an injured friend in a supermarket. When you ask: ‘what happened?’ the first friend waffles on endlessly with irrelevant information, and you get bored before you get to the answer. The second friend focuses only on describing the injury and the implications, leaving you in the dark about how it occurred, and who or what was involved.

Taking a typical example of a case report, which starts with a case name and plunges into the facts, Mr Garner also points out how this often “requires a fair amount of readerly exertion. And no reader appreciates having to work harder than the writer has worked (or should have worked) to make things clear.” Indeed, if the report is published online, the reader can surf away from your article and find another lawyer with a more engaging style.

On the other hand, an example which lacks all the facts is likely to be “too abstract and too inscrutable to be really convincing” and risks the same fate, as your reader surfs away to find one with the detail which they need.

A third example provides a model account and Mr Garner sums up his formula as:

To the first point of explaining the legal principle, I might add a few other ingredients which help the reader to assess the potential usefulness of the article quickly:

When case reports appeared only in law journals, it was safe to assume that you were writing for an audience of lawyers who were interested in both sides of the argument and who had a certain level of knowledge in the area of law.

Nowadays, your case report might be found online by someone looking for a lawyer with expertise in a particular problem. In regard to property litigation for example, it will be helpful to know at the outset if the case outcome was favourable to the landlord or the tenant.

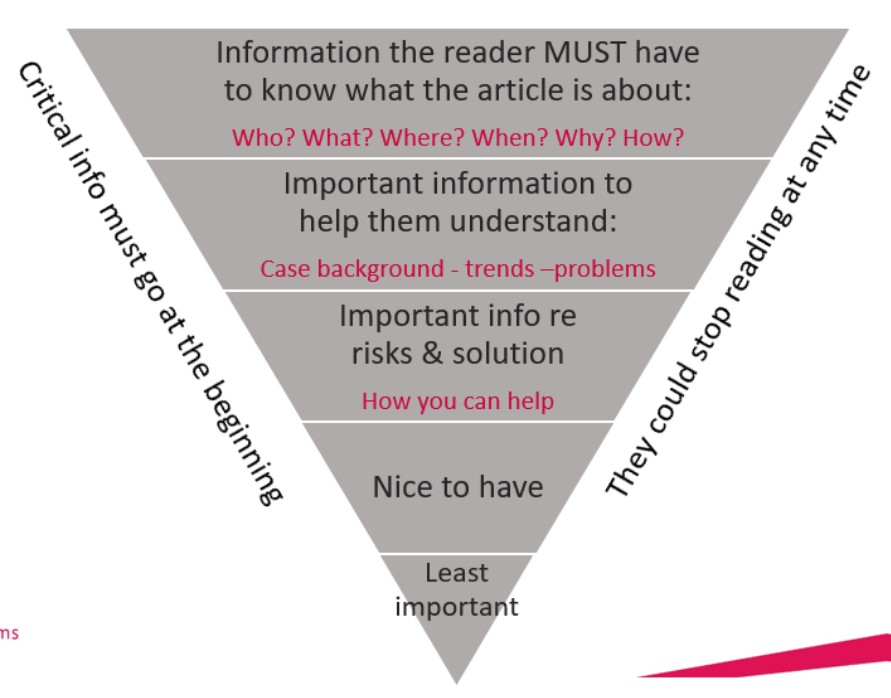

The news pyramid for legal content on case law

The opening paragraph needs to function like an executive summary. Making the punchline clear from the outset can seem counter-intuitive but this I how journalists are taught to cover a news story, working on the basis that the reader can leave the article at any time – a formula known as the ‘news pyramid’.

Of course, unlike a contract, there is no obligation to read to the end of an article on case law and the objective is to keep the reader onboard for as long as possible.